Of frequency delays, ghost delays and Aetherborne

“god gives his hardest tasks to his strongest soldiers” - Ryan Letourneau

“take a look at these hands” - Stretch armstrong

Prologue

A while back I was chatting to Geraint (of Signalsmith fame) about possible approaches to emulating a spring reverb fully algorithmically - he asked how I felt about latency…

A bit of background, I listen to a lot of rocksteady, dub and roots reggae, and was initially aiming to make a “dub spring” sort of thing, maybe with a way to “twang” the springs as it’s playing back, so I

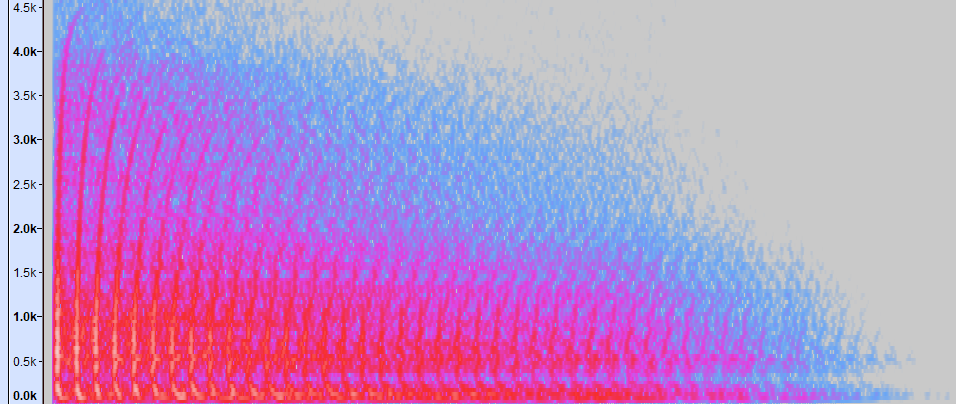

I started looking into spectrograms of spring IRs named things like “KingTubbyIR1.wav”, to get an idea of what I was even hearing and what gave it its character.

The pattern here is pretty immediately obvious, what I initially called “hook” shapes losing high end each repeat, layered on top of a bunch of diffuse “wash”

(I later found out the “hooks” are usually called chirps, so lets roll with that from now on). It also weirdly kinda looks like a spring if you’re creative, and need to get your eyes tested, and don’t think about it too hard.

What this means though, is that the characteristic “twang” of a spring is a frequency domain chirp, and a frequency domain chirp looks like it uses some curved distribution to delay each sine/cosine component of a spectrum by a slightly different amount.

So far so good, time to spam Geraint’s dm-s with screenshots of spectrograms and a bunch of question marks, and Geraint, with the patience of a very patient saint, suggested looking into….

Frequency Domain Delay

So STFTs right? Whats up with that? Aren’t they just slightly more annoying to think about ways of splitting a signal into sines and cosines, a kind of extra version of a regular fft? That you unfortunately have to use for real time applications??

Well yeah, and straight up I had such a horrible time trying to implement my own that I nabbed Geraint’s implementation from his SignalsmithDSP library, threw it all into a single header, and rolled with that instead.

The other (and in my opinion much radder) thing about STFTs is that you can think of them as not just sines/cosines, but as a filter bank of $N / 2$ bandpass filters, where $N$ is our FFT size, all running at a sample rate of our hop size $H$. All of a sudden you’re into a world of bands

instead of a world of boring regular floating point samples, and you can pretty much apply any processing there you want, with the caveat of everything now needing to be a complex number for any maths you may need to do.

An aside with this that’s still tripping me up, is that while yeah, all thats true, I’m glossing over a step. Secure your socks firmly to your sock receptacles, we’re doing m a t h s.

The Cha Cha Phase Twist

So (and depending on your background with this stuff you might have to trust me here) you can write the formula for an STFT as follows:

$X_m(\omega_k) = \sum_{-\infty}^{\infty}[x(n)e^{-j\omega_kn}]w(n - m)$

So what’s going actually going on here? First lets define some terms. $X_m(\omega_k)$ is the spectrum we’re producing, $x(n)$ is our time domain signal we want to transform, $e^{-j}$ is the “complex exponential” (euler’s number to an imaginary power), $\omega_k$ is a term relating sample rate and fft size, $n$ is a time, $m$ is a delay, and $w(x)$ is our window function. We’re essentially repeatedly calculating the DTFT, and then sliding over by $H$ samples.

side note: from euler’s formula, $e^{j\theta} = cos(\theta) + j sin(\theta)$, and in the case of the complex exponential, $e^{-j\omega t} = cos(\omega t) + jsin(\omega t)$, so there’s an argument to be made for writing the entire stft out using sin and cos instead of euler’s number for clarity and intuitiveness, but I digress..

take a breath

Cool, we know roughly what the symbols under the dresser mean, and have ballpark idea of what the stft does, why does this matter? The thing is with this configuration, our signal is being kept constant, and we’re sliding a window along it. That’s kinda dumb right? This thing is supposed to be realtime. So what we can do instead is rephrase as

$X_m(\omega_k) = \sum_{-\infty}^{\infty}[x(n + m)e^{-j\omega_kn}]w(n)$

and now we’re sliding the signal along, while the window is held in place. The problem is, now the $e^{-j\omega_kn}$ term doesn’t get adjusted, as technically it should be $e^{-j\omega_kn + m}$. So to compensate, we need to apply a phase twist to our band when we do our processing.

So “applying a phase twist” sounds pretty fuckin metal right? So it’s pretty disappointing that it literally just involves multiplying by another complex exponential. That being said, finding WHICH complex exponential to multiply by is where I’ve been getting caught, so take the following with a grain of salt, (and I’d be remissed if I didn’t cite Geraint for this, especially the part about actually calculating the phase shift, I’m essentially rephrasing his explanation).

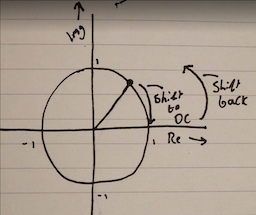

First off, it’s kinda helpful to understand WHY a phase shift is a multiplication by a complex exponential. Because we’re dealing with complex numbers, if we move to polar coordinates its pretty intuitive to think of these complex numbers as rotations around the unit circle in the imaginary plane, but even more than that, as mentioned earlier, using euler’s formula we can show that all of this abstract euler’s number business is just talking about a combination of sines and cosines, which, yknow, sines and rotations go pretty hand in hand.

all of this to say that multiplying by $e^{j\theta}$ will spin your value along the unit circle by theta radians. So we’re essentially trying to “spin” our bin to DC (the 0th bin’s phase) to do our processing, then spin it the exact inverse to get it back to normal.

For example then, lets say we’re dealing with a frequency of $0.2 f_s$. We can find its phase using $2\pi b_i 0.2$, where $b_i$ is our bin index. We need to account for hop size here, seeing as we’re using an stft which has overlapping and other self-hatred triggering properties. so to link hop size into our phase calculation, we can say that the phase at block number $p$ is $2\pi (pH) 0.2$ ($p$ increments each hop, just a way of dealing with the overlap). We can get the central frequency of bin $b_i$ with $b_i / N$.

So combining the two, we can find the phase of a bin with $2\pi (p * H) * (b_i / N)$, lets call that $S$, for shift. SO then to do our phase twist, we can just multiply our value by $e^{-j S}$, do our processing, then multiply by $e^{j S}$ to get back to the original phase.

Here’s a horrible drawing to illustrate it:

take a breath, it’s time for

The actual delaying

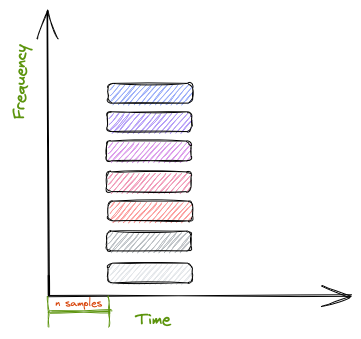

Now we’ve gotten an idea of the underlying workings and practical considerations for this, we can move onto the fun stuff. A regular delay $z^{-n}$ just delays your signal by $n$ samples, so anything that goes in comes out $n$ samples later. The equivalent to this in the frequency domain is to delay each bin by $n$ samples.

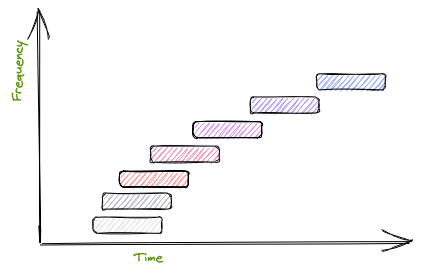

The cool thing about being in the frequency domain though, is that the delay times for each bin don’t need to be the same, so by delaying each bin by a slightly higher amount than the previous bin, we can get to this kind of idea:

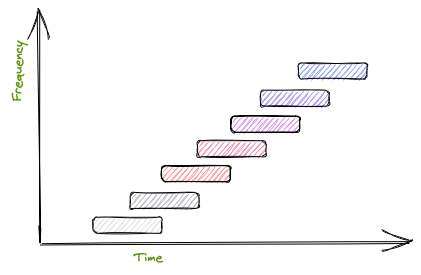

If we change the distribution of the delay times from “slightly more than the previous bin’s delay time” to “twice the previous bin’s delay time”, we get this, which is approaching the shape of the chirp we saw in the spring’s impulse response earlier.

Remember earlier I mentioned that we’re treating the STFT as as bank of bandpass filters? What we’re doing here is delaying each band by a different amount, which is effectively going to delay the harmonic components of our signal by different amounts.

To chirp or not to chirp

Practically with this, I’m still struggling to get the phase twist hellscape to actually sound right, but it does also delay things without it, just not really “correct” as the phases are out of whack. Moving on though, this technique gets you a chirp, which was what I wanted. So following the fourier stuff, back in the time domain, I tried just shoving a datorro plate (more on those bad boys in a later post) onto the output of the ISTFT, and just kinda prayed it would sound good.

It did have the spring “twang” but pretty much without any of the other spring stuff (I didn’t mention it earlier but there’s quite a clear periodic thing going on in the low end of the spring), and I’m sure I could have (and still might at some point) figured it out, but what really jumped out at me was how fucking cool it sounded with long delay times.

Conceptually, this technique of incrementally increasing delay time is going to be equivalent to doing a sweep from 0 to nyquist with a bandpass filter - the delay time distribution is dictating how the sweep moves, kind of like automatic automation. That in and of itself has a nice “envelope follower” feel to it, but the high end is where the magic happens.

With an increasing delay time each bin, the highs obviously get delayed by the most, and if you’re playing into it you’re probably playing continuously, so what you end up with is a cumulative “twinkle” in the high end with an almost windchime quality, at frequencies that are always pretty sympathetic to your input signal. Messing around with the max bin to delay helps a lot, but beware of the

G H O S T D E L A Y

This is very much a juce grievance, and probably not gonna be a very long section, but it pissed me off enough that I feel the need to talk about it. When I was testing the frequency delay stuff, I was finding that after maybe 40 - 60 seconds, a horrifying spectre would appear behind me and stab me in the neck repeatedly, and also I’d hear super delayed versions of what I played 40 to 60 seconds ago. I was capping the max bin for the delay at $N / 4$, so anything above that bin would have a delay of 0, right?

WRONG SO WRONG if you give a juce::dsp::DelayLine a delay time of zero, it kinda just delays by however much it wants. I haven’t done anything scientific, but I’d ASSUME it’s gonna delay by whatever you give it for its maximumDelayInSamples. Pretty easy to get around especially as you’ll probably have a struct that handles two delay lines at once (one for real, one for imaginary), so you can just get it to return the last pushed sample if its got a delay time of 0, but it’s a pretty cool way of gaslighting yourself into thinking you’re having auditory hallucinations, so that’s cool, and totally didn’t take me 3 hours to find…

Aetherborne, and the immaculate conception, or, Twinkle Twinkle Wet Guitar

The “twinkling” high end idea got me thinking though, it’d be cool to try and isolate, or at least accentuate that effect, along with some “ambiance” (and by ambiance I definitely just mean reverb).

Then I started thinking about what would happen if I put a reverb on each band of an STFT, with slightly different params on each, or if I just put reverb on the high bins, etc etc, and got to work prototyping.

At the moment it’s the frequency delay idea, with a default param datorro reverb on each band, so nothing TOO exciting, but as well as varying the params per band, it’d be cool to try and add some cross feedback between bands (although keeping it stable is probably gonna be the subject of the next post here…).

At any rate, its still early days on it, so I’ll sign this off with a clip of it in action:

Thanks for reading, really means a lot, I’m hoping to make these more regular, as a kind of unhinged dev log, so until next time!!! - Syl